The Work of Things

Shifting Ground Symposium, Material and the Immaterial Panel with Zavisha Chromicz, Omar Badrin and moderator Sarah Quinton, 2022. Courtesy of Harbourfront Centre.

Michael Prokopow considers the labour that goes into making.

Any formal consideration of material culture — the study of human-made or modified objects — must take into account the means by which a thing comes into being. The transformation of materials, raw or processed, into entities that respond to a need is arguably an everyday negotiation. Oftentimes, the processes of labour involved in the making of something seem to matter less than the thing itself. There is something about the tangible fact of an object: its immediacy, utility, appearance and so on. These can, even when eliciting judgements about workmanship and gradations of quality, obscure a consideration of fact of the skills and commitment needed to bring anything into existence and use.

Here, the idea of use does not draw distinctions between objects, especially in the realms of what is considered art, and what anthropologist Esther Pasztory describes as “non-art.” The regular fact of unequal attention being given to all manner of things without consideration of them as the consequences of completed processes of labour invites consideration. How is it that human agency and intention in design thinking and object production elicits such scant attention?

While I have long been concerned with questions of the work required to make objects, my renewed interest in this question (arguably as much ontological and ideological) was the result of a comment made by curator Sarah Quinton at the 2022 Shifting Ground Symposium in Toronto, Ont. Quinton was guiding a discussion with the artists Omar Badrin and Zavisha Chromicz, each of whom engages with labour intensive practices; Badrin crochets three dimensional, often anthropomorphic objects, while Chromicz creates visually rich assemblages comprising of a wide variety of textiles, including some found in thrift stores.

Shifting Ground Symposium, Material and the Immaterial Panel with Zavisha Chromicz, Omar Badrin and moderator Sarah Quinton, 2022. Courtesy of Harbourfront Centre.

The conversation had turned to the subjects of knitting, piecework and making, and more specifically, to doilies (the once requisite and now nostalgically, circumstantially favoured lacy coverings for tables). Quinton noted that despite these objects reflecting a level of skill and time investment, they have little actual market value. Notwithstanding any sentimental value that may be attached to them and other similar, most likely, “home-made” items, there was the acknowledgement of how, were it possible to know the number of hours required to make a doily, the (overwhelmingly female) labour would unquestionably be undervalued and undercompensated.

Ivonne Hernandez Farias, Red Leaf Doily, 2013. Cotton, 115 cm diameter. Courtesy of the artist.

And in these realities, there lie several matters of importance. First, there are the entwined issues of the means by which such skills are acquired and by whom. The actualities of what has historically been labelled “women’s work” is but part of the long established division of labour by way of gender enforced by patriarchy and the structures of traditionalist heteronormativity. Arguably, the faded social standing of doilies can be explained by shifts in taste and changes in domestic rituals, does not diminish the implications of the time involved to make them and their diminished use value (tied to changes in domestic trends, tastes and modes of living).

Ivonne Hernandez Farias, Red Leaf Doily (detail), 2013. Cotton, 115 cm diameter. Courtesy of the artist.

However, there remains the larger matter of the unseen or under-considered economic and social status of all objects and the attending invitation to engage in ideological conversations about labour and its value.

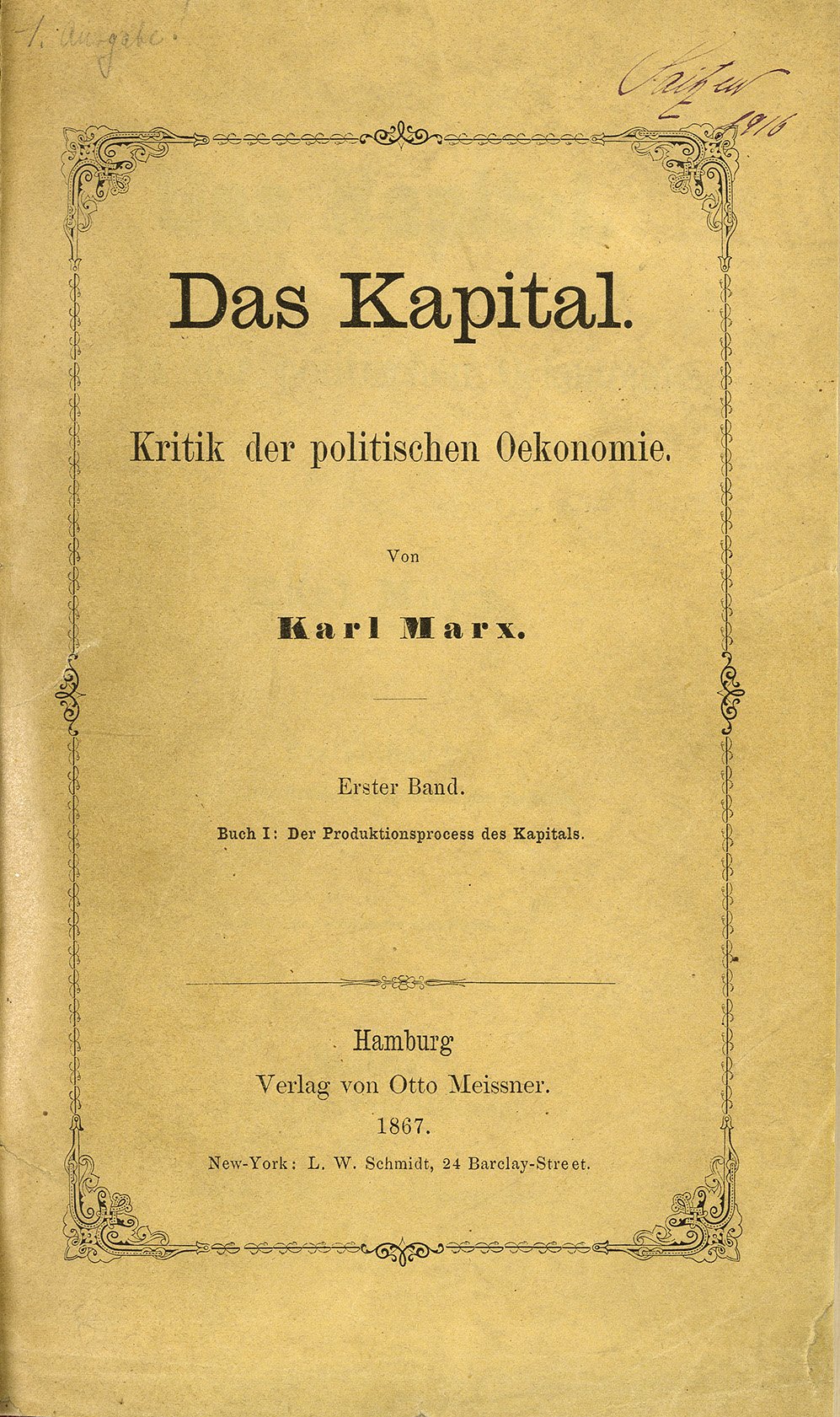

The labour theory of value — proposed by economist Adam Smith, and later espoused by Karl Marx in the 19th century and Thomas Piketty in the 21st — considers the often unsung importance of work in the making of goods. It suggests how, in the context of consumption and possession, the often transfixing power of things can result in how it is actually produced from conception to fabrication. For it is in each individual object — meaning every single thing crafted by people across history — that the structures of culture and economic relations may be found.

Karl Marx, Das Kapital, 1867. COURTESY OF ZENTRALBIBLIOTHEK ZÜRICH and WIKIPEDIA CREATIVE COMMONS.

Too easily, are the sequential factors of the marshalling of resources for the production of envisioned goods insufficiently considered because of the seductive powers of the finished objects in the contexts of markets and the privileging of consumption. By acknowledging and seeking to know the stories that underpin the tangible world of things, worlds of people, circumstances and experiences can be considered.

In simply taking the time to consider how something has come into being — whether a granite paver, brick, fork or wool blanket — there is the possibility of acknowledging past lives and their worlds. In taking the time to think about the labour that continues to make the material world possible — from the Chinese factories to Bangladeshi sweatshops, to British potteries and American ateliers, to workshops and armchairs — the aesthetic and material complexity of the world of things may be critically contextualised and humanely illuminated.

This article was published in the Spring/Summer 2023 issue of Studio Magazine