Object Stories

Sally-Lilly

Many things upset me. Pulp floating in my lemonade, dead flies on the window sill, the constellation of old chewed gum stuck to the walls of my teenage sister’s bedroom. These things caused revulsion and wonder, manifesting as little waves of nausea that lapped at the edges of my serene self. I was seven, sensitive to things that didn’t fit neatly into categories. Sally-Lilly was like that. The doll was given to me before I was born, though her presence did not take root in my psyche until I began to experience ambivalences. Her two heads, and two opposite natures, were connected in the middle by a thick torso. Sally was the brown-haired, wide-awake one. She was fun and silly but not very smart. Lilly was the pale, sound-asleep one. She was sweet but tragic, with the tendency to disappoint expectations. Sally became Lilly and Lilly became Sally with a flip of their shared, double-sided skirt. I often felt very differently about them. My mother, glancing into my bedroom, might’ve caught on my face an expression of stricken tenderness. Other times, a smear of disgust. I might parade her in front of friends, show off her strangeness, allowing them to undress her and laugh meanly at her exposed, unnatural body. Or, I’d hide her from prying eyes. She was special. Her soft hand-stitched selves, I knew, were more true and real than any of the plastic dolls my friends had. She was a beautiful, pitiable treasure. My own daughters play with her now. I never told them about my childhood feelings towards her, but I watch their faces carefully. There’s a tag sewn onto Sally’s back—‘Handmade by Evelyn Macphail.’ Who is Evelyn Macphail, my daughters want to know. She lived down the street, is my answer. She’d have me over for crust-less jam sandwiches and sugary tea. She’d take off her apron and accompany me down the front steps when it was time for me to go; so kind and so absolutely oblivious to the powers her needle and thread invoked.

Little Black Mug

8 or 9 years ago, when my mom had the kids, my husband and I decided to drive out to the ceramic department’s year-end pottery sale. We thought it would be the perfect opportunity, since it’s generally a drag to take kids to those sorts of things. We joined the people who milled around, carefully flipping bowls over to read the name on the bottom, testing the weight of platters by lifting them slowly up and down. We conferred, we murmured, enjoying the ease of kid-free communication, the chance to make focused evaluations, the fact that these things in our hands—refined, carefully made objects—were not our soggy-bottomed, milk-dribbling, wriggling children. My husband even took a few mugs for ‘test drives’; performing the motion of taking a sip, stopping just short of touching the rim to his lips. His morning coffee, he said, deserved the best. My eyes scanned the tables. Amongst all the vessels, like so many round, open mouths, was a small uniquely shaped mug—black with a pale turquoise interior. I picked it up and immediately had to laugh. There was something darling about it, but it was completely off balance, lilting to one side as though suffering a slight scoliosis of the spine. The handle, made from a small loop, was affixed too low on the body. I could barely get a finger through. To hold it I had to pinch the outside of the handle, like I would a delicate teacup. I was justabout to turn to my husband and say, “Look at this one! The poor thing! It’s a perfect failure!” These exact words—perfect failure—were sitting on the tip of my tongue when I heard a voice. “Oh!” a young man exclaimed. “I made that one!” I looked across the table. A young man was behind the cash box, his youthful skin flushed with pleasure, his blue eyes clear as swimming pools, his hair curling from his forehead in downy, lion-like waves. “I’ll take it!” I said, in a voice that came out far louder and much more emphatically than I intended. The young man shone brighter, rosier, his face a perfect beacon of earnestness. “It’s so unique!” I barked. “Thanks!” he said, “I really like making mugs!” My husband, bless him, didn’t say a word as I paid the young man the amount on the price tag—$40.00. But I could feel his irritation. He knew the mug was deformed after just one glance. We’ve moved houses several times since that sale, and across the country once. My husband groans every time he packs or unpacks that mug. And he groans even louder when he sees me using it, sipping my coffee very slowly, keeping it nestled between forefinger and thumb so it doesn’t topple over, concentrating on the awkward grasp its tiny handle requires.

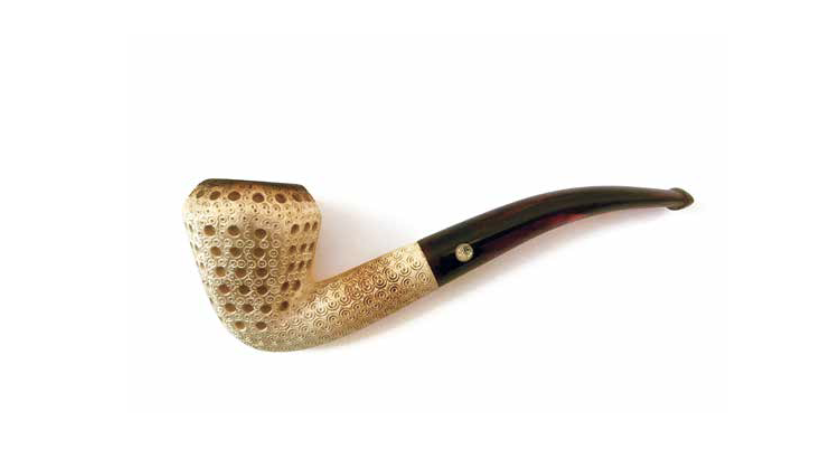

Meerschaum Pipe

My friend Tim gave me this pipe the day I turned 21. The white used to be pristine, but Turkish Sepiolite is like stiffened foam. It absorbs the colours of burning tars. First yellow, then orange, then all the pretty ambers. Tim and I had a Friday tradition—walk down Carlton to Thomas Hind’s Tobacconist. Buy some lightly flavoured Cavendish. Sit and smoke on the muddy banks of the Red. We used the 3 pinch method, filling the bowls with exaggerated solemnity. We sat on a bench so old it was growing moss, every square inch scarred with carved initials and lines of poetry: I once was here but now I’m gone I left my name to turn you on – Kayla M. (whore), Marcus Penner (loser), Jason Lowry (dick). It was the perfect spot to sit and view the sorry old Red, swollen with wormy catfish and mooneye, and the occasional dumped body too, weighted and wrapped in plastic. They dragged the river first, in those days, when someone went missing. We lived the student life—one set of dishes each and a few stacked milk-crates for Dylan records. We had no business indulging in such an expensive hobby. But Tim had a gift for enjoying life. He was attentive to everything—the thick, consistent smoke the pipe produced, the slope of its stem, the lattice pattern. The rest of us barged through life, but Tim was a deer in the forest—ears alert, eyes wide. He noticed the tinkling of the bell over the shop door, all the leafy and leathery aromas, the tobacconist’s gravelly voice. Tim liked all these things. They were part of the story, part of the lead-up to our Friday smoke. He liked to think about Sepiolite in its soft, formless state, pried from dark tunnels to harden in the sun before finding its own exquisite figure in the hands of a Meerschaum carver. He liked how conversation slowed when puffing away, how less words said more, how any of his present turmoils settled down a little, into their place in history. He liked the presence of Kayla, Marcus, and Jason there, the Turkish miner and carver, the tobacconist, the two of us, even the latest plastic wrapped somebody sunk down into the watery weeds. He liked all the strands of the grand story moving closer and closer together. He made rituals out of everything, I think, to slow down the flood of sensations, to control their pace. I lost track of Tim, and I don’t smoke much anymore, but when I do, I think of him, the wearing out of old friendships, the young selves we used to be, two skinny kids floundering on the edges of adulthood.

This article was published in the Fall/Winter 2018-19 issue of Studio Magazine